THE NEW TESTAMENT WRITERS: WHY THEY WROTE HOW THEY WROTE November 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Lascelles G. B. James All rights reserved

Source: The New Testament Writers

THE NEW TESTAMENT WRITERS: WHY THEY WROTE HOW THEY WROTE November 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Lascelles G. B. James All rights reserved

Source: The New Testament Writers

Importance of studying Hebrew Words

By Jeff A. Benner

Relationship between words

What do all of the words, astronaut, astrology, astronomy, asteroid, starlet, starfish, stellar and asterisk have in common? They are all related to “stars” and each of these words is derived out of the ancient Greek word “aster,” meaning “star.” These same types of connections between words can be found in the Hebrew language, however, from our modern Western perspective, the connections between the words may not be as apparent? We may understand the connection between hot and sun, but would we connect these two words with bag, cheese, crave and shake? Most likely not, but someone from the ancient Near East, the land of the Bible, most certainly would have.

Cheese, a craved delicacy of the ancient Near East, was made by placing the milk of a sheep or goat in a bag made from the skin of a sheep or goat. The bag is then hung out in the heatof the sun, and shaken. The skins of sheep and goats have a natural enzyme that is released when heated and shaken that separates the whey (water) from the curds (cheese).

Bedouin making cheese from a Goat skin bag

As we have demonstrated each of these words are culturally related, but in addition, they are all etymologically related as they each come from the same root word חם (hham), meaning “hot.”

| חם | hham | Hot | ||

| חמה | hham’mah | Sun | ||

| חמת | hhey’met | Skin-bag | ||

| חמה | hhem’ah | Cheese | ||

| חמד | hha’mad | To Crave | ||

| חמס | hha’mas | To Shake |

Each Hebrew word is related in meaning to other words, and these words are themselves related in meaning to other words and roots. By studying related words and their histories, we can better define them within their original context.

Root system of Hebrew words

Like a tree with its roots, trunk, branches and leaves, the Hebrew language is a system of roots and words, where one word and its meaning is the foundation to a number of other words whose spelling and meaning are related back to that one root.

As an example, the root מלך (M-L-K) means “rule.” This root can be used as a verb meaning to rule, or as a noun meaning a ruler, or king. Other nouns are created out of this root by adding other letters. By adding the letter ה (H) to the end of the root, the word מלכה(malkah) is formed, which is a female ruler, a queen. By adding a ו (U) to this feminine noun, the word מלוכה (malukhah) is formed meaning “royalty.” By adding the letters ות (UT) to the end of the root, the noun מלכות (malkut) is formed meaning the area ruled by the ruler, the kingdom.

By studying the relationship between words and their roots we can better understand the meanings of these words within their original context. Let’s take 3 English words found in English translations of the Bible: Maiden, Eternity and Secret. These three words are, from our interpretation, three much unrelated words. But let us examine the Hebrew words behind these translations: עלמה (almah), עולם (olam) and תעלמה (te’almah). Each of these words share the same three letters: ע (ayin), ל (lamed) and מ (mem, the letter “mem” has two forms,ם when it appears at the end of a word, and מ when it appears anywhere else in a word).

The Hebrew triliteral root A-L-M

Rather than perceiving them as different and independent words, we need to recognize that there meanings are related because they each come from the same root. By interpreting these words in context of their root relationship, we are able to uncover their original meanings.

The root עלם (A-L-M) literally means beyond the horizon, that hazy distance that is difficult to see. By extension it means to be out of sight, hidden from view. עלמה (almah) is the young woman that is hidden away (protected) in the home. עולם (olam) is a place or time that is in the far distance and is hidden to us. תעלמה (te’almah) is something that is hidden away.

Besides being able to find the common meaning in different words of the same root, we are also able to distinguish between different meanings of words that come from different roots. For instance, there are two Hebrew words translated as “moon.” One is ירח (yere’ahh), which comes from a root meaning “to follow a prescribed path” and is therefore used for the motion of the moon. The other is לבנה (lavanah), which comes from a root meaning “to be white” and is therefore used for its bright appearance.

When we ignore the Hebraic definitions of the words in the Bible we miss much of what the text is attempting to tell us.

Proper Biblical Interpretation

On a frequent basis we attach a meaning of a word from the Bible based on our own language and culture to a word that is not the meaning of the Hebrew word behind the translation. This is often a result of using our modern western thinking process for interpreting the Biblical text. For proper interpretation of the Bible it is essential that we take our definitions for words from an Ancient Hebraic perspective. Our modern western minds often work with words that are purely abstract or mental while the Hebrew’s vocabulary was filled with words that painted pictures of concrete concepts. By reading the Biblical text with a proper Hebrew vocabulary the text comes to life revealing the authors intended meaning.

While the Hebrew word ברית beriyt means “covenant” the cultural background of the word is helpful in understanding its full meaning. Beriyt comes from the parent root word בר (bar) meaning grain. Grains were fed to livestock to fatten them up to prepare them for the slaughter. Two other Hebrew words related to beriyt, and also derived from the parent rootbar, can help understand the meaning of beriyt. The word ברי beriy means fat and ברותbarut means meat. Notice the common theme with bar, beriy and barut, they all have to do with the slaughtering of livestock. The word beriyt is literally the animal that is slaughtered for the covenant ceremony. The phrase “make a covenant” is found thirteen times in the Hebrew Bible. In the Hebrew text this phrase is כרת ברית (karat beriyt) and literally means “cut the meat.” When a covenant is made a fattened animal is cut into pieces and laid out on the ground. Each party of the covenant then passes through the pieces signifying that if one of the parties fails to meet the agreement then the other has the right to do to the other what they did to the animal (see Genesis 15:10 and Jeremiah 34:18-20).

The English word “faith,” is defined as “confidence or trust in a person or thing; belief that is not based on proof,” but this is not the meaning of the Hebrew word אמונה (emunah), which the King James Version translates as “faith” in Habakkuk 2:4, ” The just shall live by faith..” The root of emunah is אמן (aman) meaning to be “firm.” Emunah means “steady” in the sense of firmness and is in fact translated this way in the King James Version in the following passage.

…And Aaron and Hur held up his hands, one on one side, and the other on the other side; so his hands were steady until the going down of the sun. (Exodus 17:12)

English definitions to Biblical words will not suffice for interpreting the words of the Bible. If we assume the English definition of “faith” to the Bible, we are going to misinterpret it. From a Hebraic perspective, Habakkuk 2:4 should be interpreted as “the just shall live by their steadiness.”

JHEA/RESA Vol 1, No. 1, 2003, pp. 149–194 © Boston College & Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa 2003 (ISSN 0851-7762)

This paper seeks to examine the meanings and challenges of academic freedom for African universities and intellectuals as they confront old and new pressures from globalization, governments, and the general public. It is argued that as the “development” University the 1960s and 1970s shifted to the “market” University the 1980s and 1990s, threats to academic freedom became less political and more economic.

The essay begins by discussing various definitions of academic freedom in Western and African contexts, then proceeds to explore the role of governments, the impact of globalization, the dynamics of internal governance, and finally the gender dimensions of academic freedom.

With the perils and possibilities of the new century, academics everywhere, including those in Africa, continue to face multiple challenges, both old and new, emanating from society and academe, which they have to negotiate carefully and creatively in order to protect their interests and promote their mission as teachers, researchers, and public service providers.

In fact, universities everywhere are undergoing unprecedented change thanks to rapid technological, economic, political, and social transformation in the wider world. As the old stabilities disappear, the question of academic freedom is being reconfigured, for the task becomes one of managing, in the new times, the creative tensions between institutional and individual autonomy, freedom and accountability, rights and obligations, excellence and efficiency.

The university’s internal and external constituencies are more pluralistic than ever, as are the networks and alliances that universities can forge, which recast questions of social responsibility and public service. The way these issues are being handled varies, of course between and among countries, but academic freedom will remain fundamental, as a functional condition, philosophical proposition, and moral imperative to the unfettered pursuit and dissemination of knowledge. Academic freedom allows universities to meet their responsibilities to society: speaking truth to power, promoting progress, and cultivating democratic citizenship.

University autonomy, academic freedom, and social responsibility are instruments of the same implement and are essential for the production of the critical social knowledge that facilitates material and ethical advancement. In this context, the notion of social responsibility should not mean acquiescence to authoritarian regimes or repressive civil society institutions and practices. Rather, it requires a commitment to progressive social causes, which, in the case of Africa, remain development, democracy, and self-determination.

African intellectuals and institutions of higher learning cannot make meaningful contributions to these historic and humanistic dreams without institutional autonomy and public accountability. The struggle for the university continues.

You can view the entire paper at the link provided

By Aryeh Wohl

from Teaching Hebrew as a Second/Foreign Language, 13

http://www.lookstein.org/retrieve.php?ID=3501176

The key element and major goal for successful acquisition of any language must be the ability to communicate, and participate in true meaning making. Following Vygotsky’s (1986) dictum, that learning works when there are ‘interactions’ between people, the communicative approach- with teacher scaffolding- offers social learning with higher order thinking skills such as analyzing, synthesizing, and reasoning. In spite of the stress on fluency and communication, there is certainly room for grammar instruction but its place in the instructional sequence and its methodology must be modified.

Although there have been many gains and improvements, resulting in new knowledge, in study of other languages, Hebrew language teaching however has remained frozen; the method most often used is still similar to grammar/translation. The status quo is retained since many administrators and boards of education, believe that what they has worked in the past is good enough, and they continue to do little to improve and advance teachers’ knowledge.

Lack of finances, in addition to lack of interest and/or missing knowledge, further impacts the inaction. A profession which begins with inadequate levels of pedagogical knowledge of language and which learning does not reflect upon its performance, falls prey to frozen, unacceptable standards.

The situation is exacerbated by poor scholarship with the Holy Texts and gaps in the connecting links with the Jewish nation and Israel, its past, present and future. Furthermore, we lack current in-service training, and most schools never answer to a higher authority. ‘No one is watching the store.’ Since no educational agency keeps an eye on the quality of instruction, it is left to the skills (or lack of) of the principal. Indeed, most principals I have come across have never been trained as language experts. Thus, current Hebrew language instruction is a case of the blind leading the lame.

This post was extracted from part of the content of this webpage: http://www.apologeticspress.org/APContent.aspx?category=13&article=860

A publication by Apologetics Press

http://www.apologeticspress.org

In 1901-1902, the Code of Hammurabi was discovered at the ancient site of Susa (in what is now Iran) by a French archaeological expedition under the direction of Jacques de Morgan. It was written on a piece of black diorite nearly eight feet high, and contained 282 sections. In their book, Archaeology and Bible History, Joseph Free and Howard Vos stated:

The Code of Hammurabi was written several hundred years before the time of Moses (c. 1500-1400 B.C.)…. This code, from the period 2000-1700B.C., contains advanced laws similar to those in the Mosaic laws…. In view of this archaeological evidence, the destructive critic can no longer insist that the laws of Moses are too advanced for his time (1992, pp. 103,55, emp. added).

The Code of Hammurabi established beyond doubt that writing was known hundreds of years before Moses.

As early as 1938, respected archaeologist William F. Albright, in discussing the various writing systems that existed in the Middle East during pre-Mosaic times, wrote:

In this connection it may be said that writing was well known in Palestine and Syria throughout the Patriarchal Age (Middle Bronze, 2100-1500 B.C.). No fewer than five scripts are known to have been in use: (1) Egyptian hieroglyphs, used for personal and place names by the Canaanites; (2) Accadian Cuneiform; (3) the hieroglyphiform syllabary of Phoenicia; (4) the linear alphabet of Sinai; and (5) the cuneiform alphabet of Ugarit which was discovered in 1929 (1938, p. 186).

Numerous archaeological discoveries of the past 100 years have proved once and for all that the art of writing was not only known during Moses’ day, but also long before Moses came on the scene.

REFERENCES

Albright, W.F. (1938), “Archaeology Confronts Biblical Criticism,” The American Scholar, 7:186, April.

Free, Joseph P. and Howard F. Vos (1992), Archaeology and Bible History (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan).

Jackson, Wayne (1982), Biblical Studies in the Light of Archaeology (Montgomery, AL: Apologetics Press).

Pfeiffer, Charles F. (1966), The Biblical World (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker).

Sayce, A.H. (1904), Monument Facts and Higher Critical Fancies (London: The Religious Tract Society).

Schultz, Hermann (1898), Old Testament Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark), translated from the fourth edition by H. A. Patterson.

Wellhausen, Julius (1885), Prolegomena to the History of Israel (Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black), translated by Black and Menzies.

Wiseman, D.J. (1974), The New Bible Dictionary, ed. J.D. Douglas (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans).

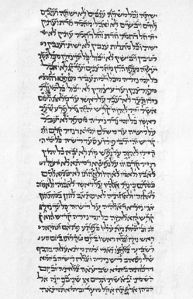

Aramaic (Arāmāyā, Classical Syriac: ܐܪܡܝܐ) is a family of languages or dialects belonging to the Semitic family. More specifically, it is part of the Northwest Semitic subfamily, which also includes Canaanite languages such as Hebrew and Phoenician. The Aramaic script was widely adopted for other languages and is ancestral to both the Arabic and Modern Hebrew alphabets.

Aramaic has served variously as a language of administration of empires and as a language of divine worship. It became the lingua franca of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC), the Neo-Babylonian Empire (605–539 BC) and Achaemenid Empire (539–323 BC), of the Neo-Assyrian states of Assur, Adiabene, Osroene and Hatra, the Aramean state of Palmyra, and the day-to-day language of Yehud Medinata and of Judaea (539 BC – 70 AD). It was the language that Jesus supposedly used the most, the language of large sections of the biblical books of Daniel and Ezra, as well as the main language of the Talmud. The major Aramaic dialect Syriac is the liturgical language of Syriac Christianity.

Most of the book of Daniel is written in Aramaic.

اَلرَّبُّ رَاعِيَّ فَلاَ يُعْوِزُنِي شَيْءٌ. فِي مَرَاعٍ خُضْرٍ يُرْبِضُنِي. إِلَى مِيَاهِ الرَّاحَةِ يُورِدُنِي. يَرُدُّ نَفْسِي. يَهْدِينِي إِلَى سُبُلِ الْبِرِّ مِنْ أَجْلِ اسْمِهِ. أَيْضاً إِذَا سِرْتُ فِي وَادِي ظِلِّ الْمَوْتِ لاَ أَخَافُ شَرّاً لأَنَّكَ أَنْتَ مَعِي. عَصَاكَ وَعُكَّازُكَ هُمَا يُعَزِّيَانِنِي. تُرَتِّبُ قُدَّامِي مَائِدَةً تُجَاهَ مُضَايِقِيَّ. مَسَحْتَ بِالدُّهْنِ رَأْسِي. كَأْسِي رَيَّا. إِنَّمَا خَيْرٌ وَرَحْمَةٌ يَتْبَعَانِنِي كُلَّ أَيَّامِ حَيَاتِي وَأَسْكُنُ فِي بَيْتِ الرَّبِّ إِلَى مَدَى الأَيَّامِ.

The Distinction between the Holy and Profane in Targum Onkelos, Megadim 43 (2005) p 73

.’ היא ‘התרגום האוטומטי 1אחת מתכונותיו הבולטות של תרגום אונקלוס לתורה אונקלוס מייחד בדרך כלל לכל מילה עברית תרגום קבוע לארמית ,שבו ישתמש בכל מקום שתופיע מילה זו .קביעות זו משווה לתרגום אופי מדויק ומקובע ,ויוצרת צמידות מקסימלית לטקסט העברי ,במינוח ,במספר המילים ובסדרן .כך יוכל לומד הבקי בתרגום לנחש מראש ,במידה רבה של דיוק ,כיצד יתורגם לארמית פסוק נתון . ניתן לומר ,כי תרגום אונקלוס הוא היפוכו של מה שמקובל לכנות ‘תרגום חופשי’. והיא 2, הנטייה לתרגום אוטומטי נבדקה לאחרונה באופן מקיף על ידי ר”ב פוזן מכונה על ידיו ‘עקיבות תרגומית’ .מסקנתו של פוזן היא ,שאכן קיימת עקיבות רבה , אם כי לא מלאה ,בתרגום אונקלוס .בספרו בודק פוזן את הכלל באמצעות היוצאים מן הכלל :הוא עומד על הסטיות מן התרגום האוטומטי ,ומחלק את הגורמים שבגללם סוטה אונקלוס מן התרגום האוטומטי הצפוי לגורמים לשוניים ולגורמים תוכניים. לצורך הבהרת ההבדל בין שני סוגי הגורמים ,נביא מספר דוגמות לסטיות מן התרגום האוטומטי הנובעות מגורמים לשוניים ,שהן בדרך כלל סטיות מתבקשות , האימננטיות למלאכת התרגום.

The Distinction between the Holy and Profane

Leviticus 10:8-11 And Jehovah speaketh unto Aaron, saying, 9 ‘Wine and strong drink thou dost not drink, thou, and thy sons with thee, in your going in unto the tent of meeting, and ye die not — a statute age-during to your generations; 10 so as to make a separation between the holy and the common, and between the unclean and the pure; 11 and to teach the sons of Israel all the statutes which Jehovah hath spoken unto them by the hand of Moses.’

Leviticus 11:46-47 This is a law of the beasts, and of the fowl, and of every living creature which is moving in the waters, and of every creature which is teeming on the earth, 47 to make separation between the unclean and the pure, and between the beast that is eaten, and the beast that is not eaten.’

Ezekiel 22:26 Its priests have wronged My law, And they pollute My holy things, Between holy and common they have not made separation, And between the unclean and the clean they have not made known, And from my sabbaths they have hidden their eyes, And I am pierced in their midst.

Translations of scripture are known in Hebrew as Targums or Targumim. However, the word Targum is used to designate a translation of a book of the Hebrew Bible into Aramaic. Before the Christian era, Hebrew lost its place as the vernacular of Palestine to Aramaic.

Rabbinic Judaism has transmitted Targumim of all the books of the Hebrew Canon with the exception of Daniel and Ezral-Nehemiah, which are themselves partly in Aramaic. The Targumim are not of the same kind. They were translated at different times and have more than one interpretive approach to the Hebrew Bible.

Targumim have been part of Jewish traditional literature since the Second Temple times.

The Targum Onḳelos or Babylonian Targun is the official Targum to the Pentateuch, which subsequently gained currency and general acceptance throughout the Babylonian schools, and was therefore called the “Babylonian Targum”

See this link:

Psalm 63

O God, thou art my God; early will I seek thee: my soul thirsteth for thee, my flesh longeth for thee in a dry and thirsty land, where no water is; 2 To see thy power and thy glory, so as I have seen thee in the sanctuary. 3 Because thy lovingkindness is better than life, my lips shall praise thee. 4 Thus will I bless thee while I live: I will lift up my hands in thy name. 5 My soul shall be satisfied as with marrow and fatness; and my mouth shall praise thee with joyful lips: 6 When I remember thee upon my bed, and meditate on thee in the night watches. 7 Because thou hast been my help, therefore in the shadow of thy wings will I rejoice. 8 My soul followeth hard after thee: thy right hand upholdeth me. 9 But those that seek my soul, to destroy it, shall go into the lower parts of the earth. 10 They shall fall by the sword: they shall be a portion for foxes. 11 But the king shall rejoice in God; every one that sweareth by him shall glory: but the mouth of them that speak lies shall be stopped.